Dinosaurs are a diverse group of animals of the clade and superorder Dinosauria. They were the dominant terrestrial vertebrates for over 160 million years, from the late Triassic period (about 230 million years ago) until the end of the Cretaceous (about 65 million years ago), when the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event led to the extinction of all non-avian dinosaurs at the close of the Mesozoic era. The fossil record indicates that birds evolved within theropod dinosaurs during the Jurassic period. Some of them survived the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, including the ancestors of all modern birds. Consequently, in modern classification systems, birds are considered a type of dinosaur—the only group which survived to the present day.

Dinosaurs are a varied group of animals. Birds, at over 9,000 living species, are the most diverse group of vertebrates besides perciform fish.Using fossil evidence, paleontologists have identified over 500 distinct genera and more than 1,000 different species of non-avian dinosaurs. Dinosaurs are represented on every continent by both extant species and fossil remains. Some are herbivorous, others carnivorous. Many dinosaurs have been bipedal, and many extinct groups were also quadrupedal, and some were able to shift between these body postures. Many species possess elaborate display structures such as horns or crests, and some prehistoric groups even developed skeletal modifications such as bony armor and spines. Avian dinosaurs have been the planet's dominant flying vertebrate since the extinction of the pterosaurs, and evidence suggests that all ancient dinosaurs built nests and laid eggs much as avian species do today. Dinosaurs varied widely in size and weight; the smallest adult theropods were less than 100 centimeters (40 inches) long, while the largest sauropods could reach lengths of almost 50 meters (165 feet) and were several stories tall.

Although the word dinosaur means "terrible lizard," the name is somewhat misleading, as dinosaurs were not lizards. Rather, they were a separate group of reptiles with a distinct upright posture not found in lizards. Through the first half of the 20th century, most of the scientific community believed dinosaurs were sluggish, unintelligent, and cold-blooded. Most research conducted since the 1970s, however, has indicated that dinosaurs were active animals with elevated metabolisms and numerous adaptations for social interaction, and many groups (especially the carnivores) were among the most intelligent organisms of the time.

Since the first dinosaur fossils were recognized in the early 19th century, mounted fossil dinosaur skeletons or replicas have been major attractions at museums around the world, and dinosaurs have become a part of world culture. Their diversity, the large sizes of some groups, and their seemingly monstrous and fantastic nature have captured the interest and imagination of the general public for over a century. They have been featured in best-selling books and films such as Jurassic Park, and new discoveries are regularly covered by the media.

Origins and early evolution

Marasuchus, a dinosaur-like ornithodiran

When dinosaurs appeared, terrestrial habitats were occupied by various types of basal archosaurs and therapsids, such as aetosaurs, cynodonts, dicynodonts, ornithosuchids, rauisuchias, and rhynchosaurs. Most of these other animals became extinct in the Triassic, in one of two events. First, at about the boundary between the Carnian and Norian faunal stages (about 215 million years ago), dicynodonts and a variety of basal archosauromorphs, including the prolacertiforms and rhynchosaurs, became extinct. This was followed by the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event (about 200 million years ago), that saw the end of most of the other groups of early archosaurs, like aetosaurs, ornithosuchids, phytosaurs, and rauisuchians. These losses left behind a land fauna of crocodylomorphs, dinosaurs, mammals, pterosaurians, and turtles.[10] The first few lines of early dinosaurs diversified through the Carnian and Norian stages of the Triassic, most likely by occupying the niches of the groups that became extinct.

Modern definition

Formal definitions are written to correspond with scientific conceptions of dinosaurs that predate the modern use of phylogenetics. The continuity of meaning is intended to prevent confusion about what the term "dinosaur" means.

Under phylogenetic taxonomy, dinosaurs are usually defined as the group consisting of "Triceratops, Neornithes [modern birds], their most recent common ancestor, and all descendants".[10] It has also been suggested that Dinosauria be defined with respect to the MRCA of Megalosaurus and Iguanodon, because these were two of the three genera cited by Richard Owen when he recognized the Dinosauria.[11] Both definitions result in the same set of animals being defined as dinosaurs, that is "Dinosauria = Ornithischia + Saurischia", which encompasses theropods (mostly bipedal carnivores and birds), ankylosaurians (armored herbivorous quadrupeds), stegosaurians (plated herbivorous quadrupeds), ceratopsians (herbivorous quadrupeds with horns and frills), ornithopods (bipedal or quadrupedal herbivores including "duck-bills"), and, perhaps, sauropodomorphs (mostly large herbivorous quadrupeds with long necks and tails).

Many paleontologists note that the point at which sauropodomorphs and theropods diverged may omit sauropodomorphs from the definition for both saurischians and dinosaurs. To avoid the instability of Dinosauria, a more conservative definition of Dinosauria is defined with respect to four anchoring nodes: Triceratops horridus, Saltasaurus loricatus, and Passer domesticus, their most recent common ancestor, and all descendants. This "safer" definition can be expressed as "Dinosauria = Ornithischia + Sauropodomorpha + Theropoda".[12]

There is a wide consensus among paleontologists that birds are the descendants of theropod dinosaurs. Using the strict phylogenetic nomenclatural definition that all descendants of a single common ancestor must be included in a group for that group to be natural, birds would thus be dinosaurs and dinosaurs are, therefore, not extinct. Birds are classified by most paleontologists as belonging to the subgroup Maniraptora, which are coelurosaurs, which are theropods, which are saurischians, which are dinosaurs.[13]

From the point of view of cladistics, birds are dinosaurs, but in ordinary speech the word "dinosaur" does not include birds. Additionally, referring to dinosaurs that are not birds as "non-avian dinosaurs" is cumbersome. For clarity, this article will use "dinosaur" as a synonym for "non-avian dinosaur". The term "non-avian dinosaur" will be used for emphasis as needed.

General description

Using one of the above definitions, dinosaurs (aside from birds) can be generally described as terrestrial archosaurian reptiles with limbs held erect beneath the body, that existed from the Late Triassic (first appearing in the Carnian faunal stage) to the Late Cretaceous (going extinct at the end of the Maastrichtian).[14] Many prehistoric animals are popularly conceived of as dinosaurs, such as ichthyosaurs, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, and Dimetrodon, but are not classified scientifically as dinosaurs. Marine reptiles like ichthyosaurs, mosasaurs, and plesiosaurs were neither terrestrial nor archosaurs; pterosaurs were archosaurs but not terrestrial; and Dimetrodon was a Permian animal more closely related to mammals.[15] Dinosaurs were the dominant terrestrial vertebrates of the Mesozoic, especially the Jurassic and Cretaceous. Other groups of animals were restricted in size and niches; mammals, for example, rarely exceeded the size of a cat, and were generally rodent-sized carnivores of small prey.[16] One notable exception is Repenomamus giganticus, a triconodont weighing between 12 kilograms (26 lb) and 14 kilograms (31 lb) that is known to have eaten small dinosaurs like young Psittacosaurus.[17]

Dinosaurs were an extremely varied group of animals; according to a 2006 study, over 500 dinosaur genera have been identified with certainty so far, and the total number of genera preserved in the fossil record has been estimated at around 1850, nearly 75% of which remain to be discovered.[4] An earlier study predicted that about 3400 dinosaur genera existed, including many which would not have been preserved in the fossil record.[18]As of September 17, 2008, 1047 different species of dinosaurs have been named.[5] Some were herbivorous, others carnivorous. Some dinosaurs were bipeds, some were quadrupeds, and others, such as Ammosaurus and Iguanodon, could walk just as easily on two or four legs. Many had bony armor, or cranial modifications like horns and crests. Although known for large size, many dinosaurs were human-sized or smaller. Dinosaur remains have been found on every continent on Earth, including Antarctica.[6] No non-avian dinosaurs are known to have lived in marine habitats or in aerial habitats, although it is possible some feathered non-avian theropods were flyers. There is also evidence that some spinosaurids had semi-aquatic habits.

History of discovery

Dinosaur fossils have been known for millennia, although their true nature was not recognized. The Chinese, whose modern word for dinosaur is konglong (恐龍, or "terrible dragon"), considered them to be dragon bones and documented them as such. For example, Hua Yang Guo Zhi, a book written by Zhang Qu during the Western Jin Dynasty, reported the discovery of dragon bones at Wucheng in Sichuan Province.[140] Villagers in central China have long unearthed fossilized "dragon bones" for use in traditional medicines, a practice that continues today.[141] In Europe, dinosaur fossils were generally believed to be the remains of giants and other creatures killed by the Great Flood.

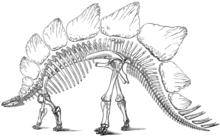

Marsh's 1896 illustration of the bones of Stegosaurus, a dinosaur he described and named in 1877.

William Buckland

The study of these "great fossil lizards" soon became of great interest to European and American scientists, and in 1842 the English paleontologist Richard Owen coined the term "dinosaur". He recognized that the remains that had been found so far, Iguanodon, Megalosaurus and Hylaeosaurus, shared a number of distinctive features, and so decided to present them as a distinct taxonomic group. With the backing of Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, the husband of Queen Victoria, Owen established the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, London, to display the national collection of dinosaur fossils and other biological and geological exhibits.

In 1858, the first known American dinosaur was discovered, in marl pits in the small town of Haddonfield, New Jersey (although fossils had been found before, their nature had not been correctly discerned). The creature was named Hadrosaurus foulkii. It was an extremely important find: Hadrosaurus was one of the first nearly complete dinosaur skeletons found (the first was in 1834, in Maidstone, Kent, England), and it was clearly a bipedal creature. This was a revolutionary discovery as, until that point, most scientists had believed dinosaurs walked on four feet, like other lizards. Foulke's discoveries sparked a wave of dinosaur mania in the United States.

Othniel Charles Marsh, 19th century photograph

Edward Drinker Cope, 19th century photograph

After 1897, the search for dinosaur fossils extended to every continent, including Antarctica. The first Antarctic dinosaur to be discovered, the ankylosaurid Antarctopelta oliveroi, was found on Ross Island in 1986, although it was 1994 before an Antarctic species, the theropod Cryolophosaurus ellioti, was formally named and described in a scientific journal.

Current dinosaur "hot spots" include southern South America (especially Argentina) and China. China in particular has produced many exceptional feathered dinosaur specimens due to the unique geology of its dinosaur beds, as well as an ancient arid climate particularly

Extinction of major groups

Main articles: Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event and K–Pg boundary

The discovery that birds are a type of dinosaur showed that dinosaurs in general are not, in fact, extinct as is commonly stated.[121] However, all non-avian dinosaurs as well as many groups of birds did suddenly become extinct approximately 65 million years ago. Many other groups of animals also became extinct at this time, including ammonites (nautilus-like mollusks), mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, and many groups of mammals.[6] This mass extinction is known as the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. The nature of the event that caused this mass extinction has been extensively studied since the 1970s; at present, several related theories are supported by paleontologists. Though the consensus is that an impact event was the primary cause of dinosaur extinction, some scientists cite other possible causes, or support the idea that a confluence of several factors was responsible for the sudden disappearance of dinosaurs from the fossil record.At the peak of the Mesozoic, there were no polar ice caps, and sea levels are estimated to have been from 100 to 250 meters (300 to 800 ft) higher than they are today. The planet's temperature was also much more uniform, with only 25 °C (45 °F) separating average polar temperatures from those at the equator. On average, atmospheric temperatures were also much higher; the poles, for example, were 50 °C (90 °F) warmer than today.

The atmosphere's composition during the Mesozoic was vastly different as well. Carbon dioxide levels were up to 12 times higher than today's levels, and oxygen formed 32 to 35% of the atmosphere,[citation needed] as compared to 21% today. However, by the late Cretaceous, the environment was changing dramatically. Volcanic activity was decreasing, which led to a cooling trend as levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide dropped. Oxygen levels in the atmosphere also started to fluctuate and would ultimately fall considerably. Some scientists hypothesize that climate change, combined with lower oxygen levels, might have led directly to the demise of many species. If the dinosaurs had respiratory systems similar to those commonly found in modern birds, it may have been particularly difficult for them to cope with reduced respiratory efficiency, given the enormous oxygen demands of their very large bodies

No comments:

Post a Comment